Reading time: 14 minutes

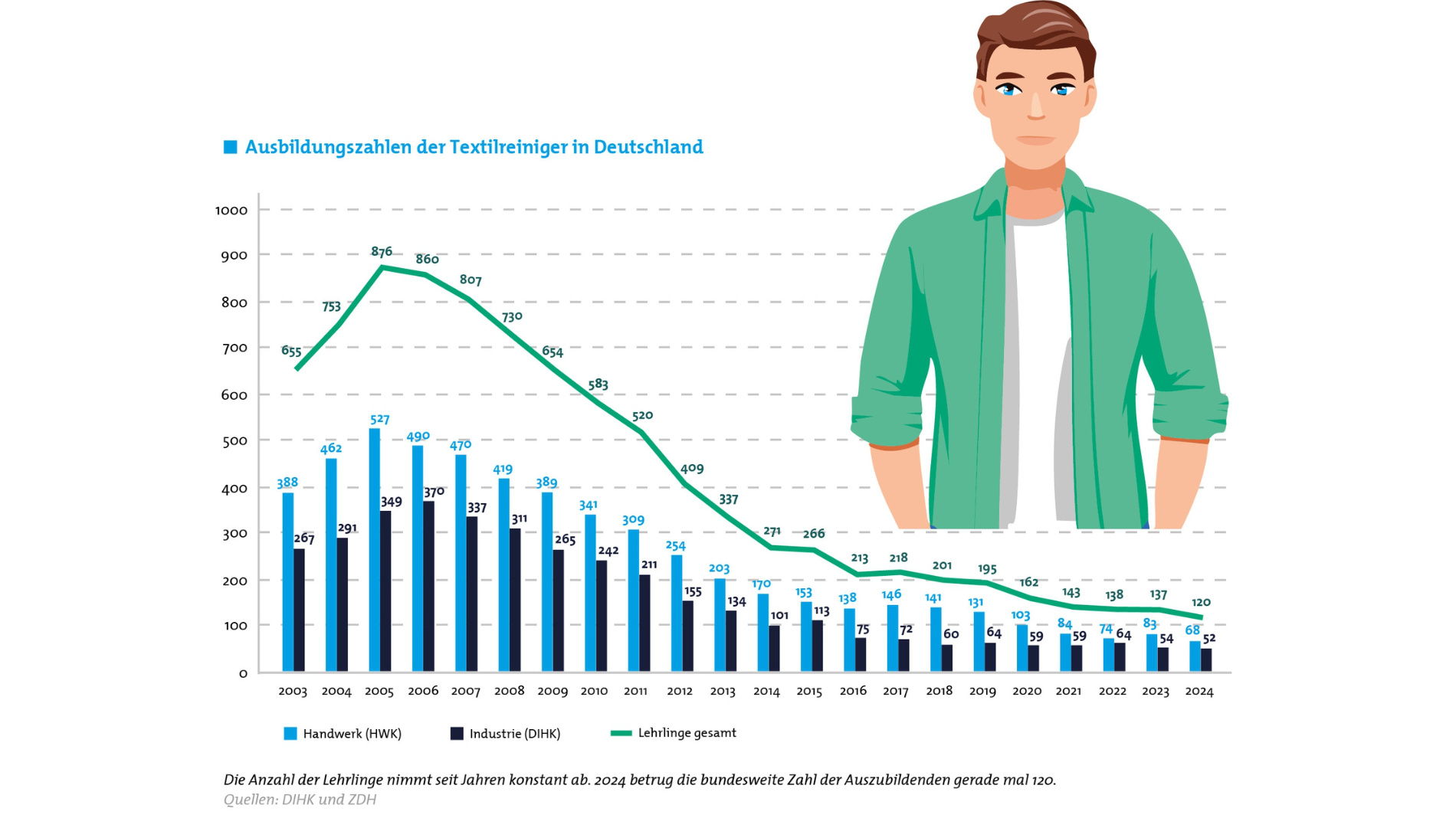

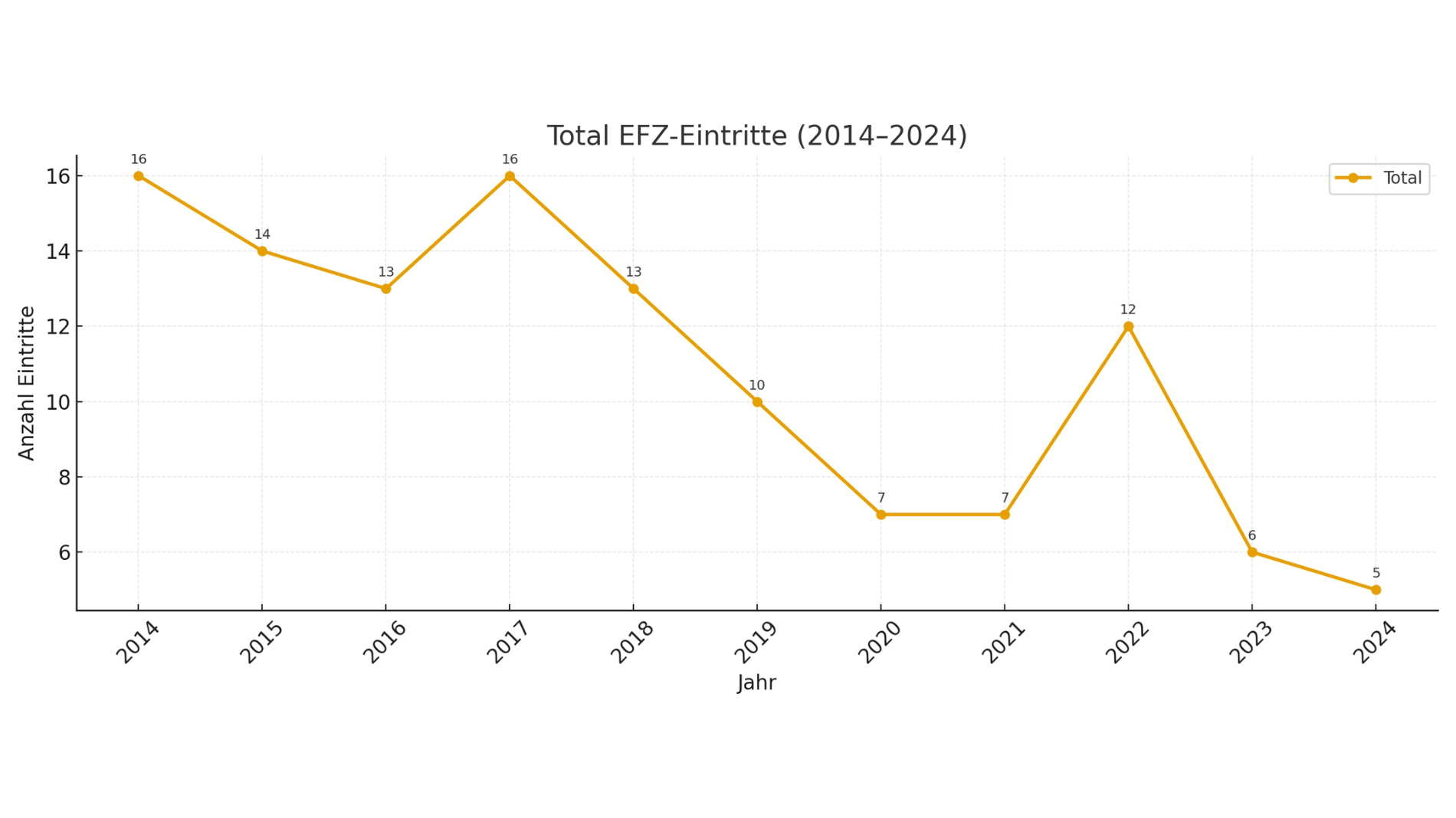

The figures speak for themselves: In 2005, there were still more than 7,000 laundry and cleaning businesses in Germany and 876 apprentices training as textile cleaners. By 2024, the number of businesses had dropped to less than half, with only 120 apprentices remaining – a decline of more than 85 percent. It is therefore hardly surprising that, in the DTV business climate survey conducted in summer 2025, 60 percent of companies reported difficulties in filling vacancies. A similar picture emerges in Switzerland: around 840 laundries, dry cleaners and textile service providers remain – yet, as of September 2025, only 25 apprentices were training as textile care specialists (EFZ). Given demographic change, an ageing workforce and the lack of young talent, there is no sign of relief in sight.

Ms Saner, Mr Schumacher, your associations represent around 1,000 textile care companies in Germany and Switzerland with more than 80,000 employees. You are in daily contact with businesses in the textile care sector. If you had to describe the current staffing situation in the industry in one sentence – what would it be?

(Both laugh)

Andreas Schumacher: It’s actually impossible to describe the situation in just one sentence, because there are so many different factors at play. For one, the small number of vocational schools has a major impact on both companies’ and young people’s willingness to train. Then there’s the external attractiveness of the profession, demographic change and the growing trend towards academic careers. All of these factors interact and reinforce one another – and in the end, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: the fewer apprentices and master craftsmen and women there are, the less training takes place in companies. But what I can say in one sentence is this: I’m confident that we will succeed in turning the trend around.

Melanie Saner: I can fully agree with everything Andreas has said.

Ms Saner, you once said, “Our profession has an image problem”. What exactly do you mean by that, and where does the textile care industry’s image problem come from?

Melanie Saner: What I meant is that many young people hear terms like “laundry” or “dry cleaning” and think: “Oh, that’s just dirty laundry – I do that at home.” I notice this at job and training fairs, when visitors come to our stand and say in surprise, “You can actually learn that? I had no idea!” Many young people have an image of textile care that doesn’t reflect reality.

What prejudices or misconceptions about professional textile care do you both encounter most often when talking to young people, their parents or outsiders?

Melanie Saner: What is really underestimated is the complexity of modern laundries and cleaning operations. It’s quite astonishing when you think about it: dirty textiles come in, are processed, and then have to be delivered clean, on time and in the right quantities to the right customer – often involving thousands of individual items every day. It’s remarkable that such a system works so smoothly.

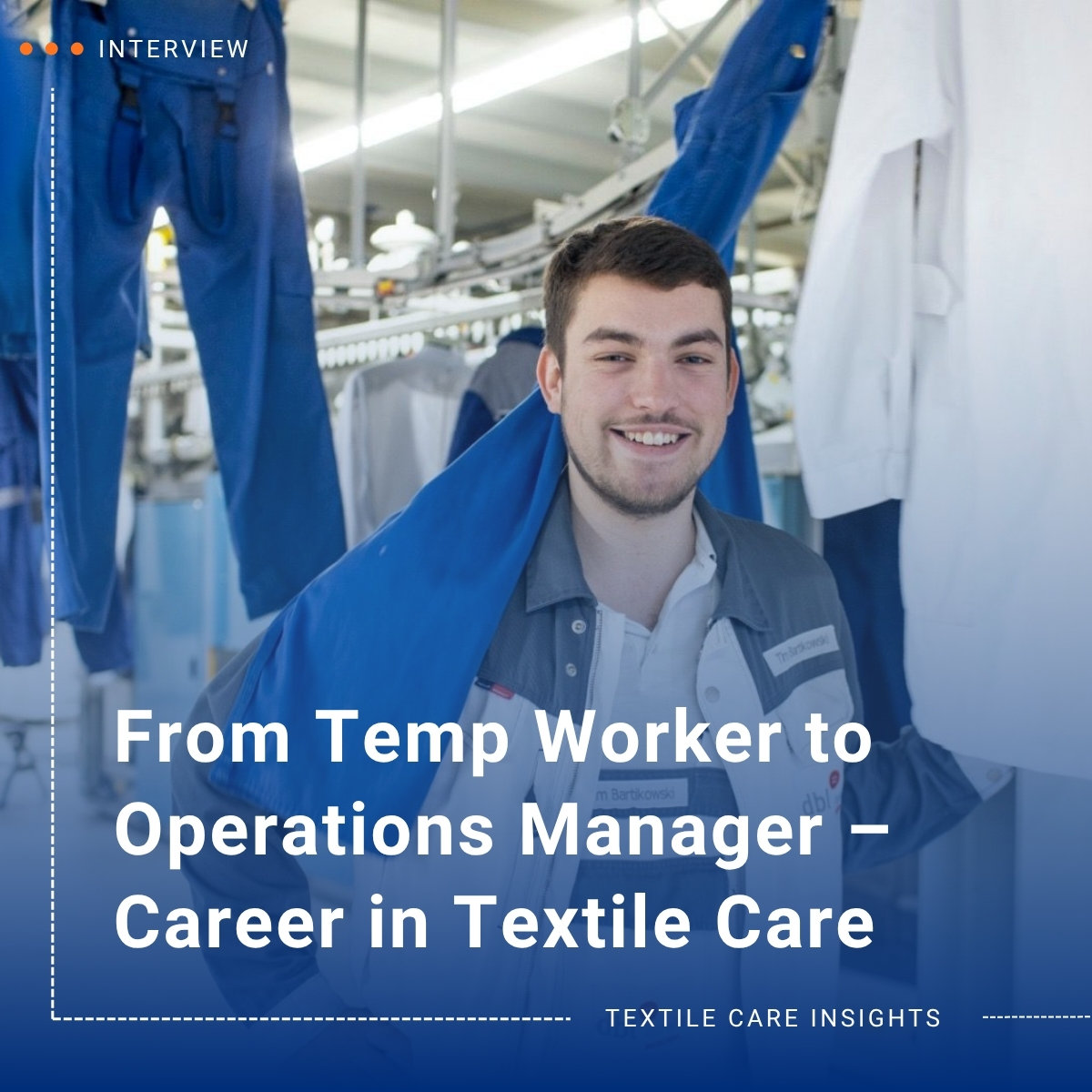

Andreas Schumacher: Some of our companies even joke that they are actually logistics firms with a laundry attached, because logistics in textile care is more demanding than in almost any other sector. Outsiders often only know the B2C side – the small dry cleaner around the corner. Many imagine someone standing at a washing machine cleaning garments by hand. But around 80 percent of textile care is B2B business, and operations today look very different. We always have to explain: think about who cleans hospital linen, hotel laundry or workwear for millions of employees – in Germany alone, that’s 80,000 people working in textile care.

The textile care sector already works with cutting-edge technology, digital processes and automation. Why is that not reflected in public perception?

Andreas Schumacher: There are countless complex processes in textile care – from cleaning and washing procedures to logistics – which makes it hard to communicate the profession’s image because it’s so intricate. To make this complexity more visible, we even discussed renaming the apprenticeship from “textile cleaner” to something more modern that better reflects the process-driven nature of the job.

Melanie Saner: We probably need to be a bit more creative in our future career marketing. As an industry, one of our most important tasks is to better inform the public – not just about training, but about textile care as a whole – so that people understand how essential our work is for society and how the industry actually operates.

How has recruitment in textile care changed? What role do Instagram, TikTok and other social media platforms play? Are companies reaching young people through them, or are initiatives such as internships, trial days or personal insights more effective?

Andreas Schumacher: In my view, our companies are doing no less on social media than others in the skilled trades. Many are active on Instagram, sharing posts from daily operations, introducing their teams and positioning themselves as training providers – some are even experimenting with TikTok. Yes, it’s a complex profession that’s not easy to communicate, but we shouldn’t sell ourselves short.

Melanie Saner: Absolutely. Social media alone isn’t enough, though. I see two key areas: on the one hand, our association’s work to position the industry with relevant topics – a sort of background noise; on the other, the companies themselves, which need to market their training places and jobs while highlighting what matters to them – such as workplace culture or sustainability. We often recommend that businesses take part in career fairs and get involved locally – for instance, by visiting schools and showing young people in their region the career opportunities textile care has to offer.

Both refer to the “International Laundry and Textile Cleaning Week”. During this event, textile care companies from France, Belgium, the Czech Republic, the United Kingdom, Germany (since 2025) and other countries open their doors for a week to present themselves as employers and training providers. The next event will take place in March 2026.

Young people today are often looking for meaningful work combined with attractive working conditions. Are textile care companies already making full use of the opportunities between purposeful work and benefits such as competitive pay, flexible hours and work–life balance?

Melanie Saner: There’s a wide variety of companies. In Swiss textile care, training contracts are generally signed relatively late. Many trainees are simply happy to have found an apprenticeship at all. But once they start, many of them discover a real passion for the profession and remain loyal to textile care.

Andreas Schumacher: As in any other sector, conditions in textile care vary greatly from one company to another. I know businesses with 280 employees and 80 different working-time models – they really make an effort to meet the many different needs of their staff. Of course, it’s a demanding job and operations have to run smoothly. That may not sound appealing to everyone, but we try to show that it’s meaningful work – essential for hospitals and care homes, and part of a sustainable industry, which certainly resonates with young people.

Sustainability is important to many young people. Textile care extends the lifespan of clothing and is therefore an important pillar of the circular economy. Can the industry use this to attract more young professionals?

Melanie Saner: As an industry, we are constantly working to highlight the importance of sustainability – although I believe there’s still potential to communicate this even more strongly in the future. Studies show that sustainability and meaningful work are becoming increasingly important as criteria when choosing a career. But it’s also true that, like previous generations, many young people still place great value on practical aspects such as workplace culture, career opportunities, pay, and location or accessibility.

Andreas Schumacher: Sustainability offers our industry many opportunities – particularly in attracting young talent. Textile care has been sustainable for decades, as our companies keep textiles in circulation, reducing pollution and the need for new textile production. Most leased textiles are made specifically for industrial laundering, ensuring high quality and durability – the opposite of fast fashion. Many companies also employ tailors to repair garments, extending their service life for as long as possible. Often, textiles no longer needed by one customer are stored for future use. That’s why we welcome the EU Commission’s initiatives promoting a circular textile economy – they help us draw more attention from young people to sustainability in textile care.

Speaking of international recruitment: in many laundries, people from a wide range of countries already work side by side. What role will the recruitment of international professionals play in future? What initiatives already exist, and what opportunities does this offer for a medium-sized industry like textile care?

Andreas Schumacher: The profile of apprentices in textile care has changed dramatically over the past ten years. If we look at first-year apprentices at vocational schools today, I would estimate that well over half now have a migration background. I know one laundry where the flags of all employees’ home countries hang on the wall – there are around 50 of them by now. We have a much more diverse and international group of trainees than we did 15 years ago. Many companies are already very active in recruiting skilled workers from abroad because they can hardly find apprentices in Germany, yet still need to train professionals. Some businesses have successfully recruited young trainees from Indonesia, Vietnam and Eritrea to train in Germany. I recently visited the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, where the German government has launched a cooperation agreement with the Jordanian government to promote international mobility for skilled workers. The DTV is taking part in this programme and has already placed seven young people from Jordan in training positions at our member companies. We plan to further expand such partnerships in the future.

Melanie Saner: It’s similar in Switzerland. We have companies employing people from up to 25 different nations. If you look at the winners of the Swiss Textile Care Championships 2025, none of the three originally came from Switzerland. Today, companies recruit young people and adults for training in a variety of ways – through special organisations, professional associations or bridging programmes.

Almost three million young people in Germany between the ages of 20 and 34 have no vocational qualification – nearly 20 percent of this age group. What opportunities does textile care have to attract these young people as career changers? And how can missing qualifications be compensated through further training?

Melanie Saner: We’re already very active in this area in Switzerland. Many adults enter the industry as career changers without a formal qualification but are eager to obtain one. For them, we offer the option of a shortened training programme, allowing them to earn the EFZ qualification within two years. In French-speaking Switzerland, more people now obtain their qualification this way than through the traditional youth apprenticeship route.

Andreas Schumacher: I can absolutely confirm that. The traditional route – someone leaving school and completing an apprenticeship – is becoming increasingly rare. On the contrary, entry paths into our industry have become so varied that we want to open up even further to alternative routes. That’s why we’re currently developing partial qualification modules in cooperation with the Central Office for Continuing Vocational Training in the Skilled Trades (ZWH). These modules are designed for employees already working in companies who want to further develop their skills. They continue to receive their salary while the learning phases are supported by the employment agency. The modules – for example in washing processes or machinery – can be completed in stages. In the end, participants reach the qualification level of a certified textile cleaner and can even take the final exam if they wish. To make textile care more attractive for academically minded people, we’ve also introduced a brand-new bachelor’s degree programme at the Baden-Württemberg Cooperative State University (DHBW) in Mannheim. It’s a three-year dual study course alternating between three months at the company and three months at the university.

Across Germany, there are now only five vocational schools where textile cleaners receive training: Neumünster, Greifswald, Berlin, Hanover and Frankfurt am Main. Are there any plans to improve this challenging situation in the future?

Andreas Schumacher: The limited number of vocational schools is certainly one reason why so few apprentices are being trained. It’s important to know that the locations of these schools are determined by the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education. Although many now offer block courses, the distances are still a challenge for both companies and trainees – especially since apprentices are often away for two or three weeks at a time. Some say it’s simply too far, and some parents don’t want their children living alone in a distant city for that long. A few years ago, we launched an initiative to reopen the vocational school in Erfurt. The head teacher was keen, and we fought hard – we even managed to gather 13 apprentices from Thuringia, Saxony-Anhalt and Saxony. Unfortunately, the ministry decided against it, saying that 13 students were below the required minimum of 15. Despite this setback, I remain optimistic that we’ll be able to preserve the existing schools. I can see that companies – both small and large – are once again placing more emphasis on training. Many say: “We haven’t trained anyone for years – now we want to start again.” Vocational schools could also benefit from international recruitment in the future, with more trainees coming from non-EU countries. Today, many companies already finance individual language courses for their trainees, but government-supported in-house language training would certainly be helpful.

In textile care, professional expertise is the foundation of customer trust in laundry quality. Given the shortage of skilled workers, the question increasingly arises as to how companies can maintain this quality. What role does automation play – now and in the future?

Andreas Schumacher: Of course, there are laundries using robots today, but they usually handle only simple tasks. Automation cannot replace skilled workers in textile care – quite the opposite: it actually increases the need for people who understand automated systems. This means new areas of training will emerge, focusing on machinery, robotics and automation.

Melanie Saner: Automation is certainly helpful, but it doesn’t replace qualified staff. If we ever reach a point where no more apprentices can be found, we’ll have to bring in people from other professions and train them further. In my view, there will always be a need for well-trained specialists in textile care.

Business succession is also a critical issue for many companies in textile care. Despite intensive searches, some find it difficult to secure a successor. What developments do you observe here, and where do you see the main opportunities and challenges?

Andreas Schumacher: An increasing number of companies are facing a generational change. Some approach us directly because they’re looking for someone to take over management. We even maintain a list of businesses searching for successors. Young people interested in taking over a company can contact us. We’ve already successfully facilitated some matches – for example, a participant from one of my master classes approached me and said: “I’d like to run my own business.” We were able to connect them with a laundry that was looking for a new managing director. This will definitely remain an important topic for the future.

Melanie Saner: Finding a successor is certainly not easy. It’s important to remember that, alongside technical skills, business knowledge and technological competence are also required. Another challenge is financing a takeover and ensuring good preparation so that the transition runs smoothly for everyone involved.

What, for you personally, is the fascination and societal importance of textile care – and why is it worth fighting for despite the current staffing crisis?

Melanie Saner: It’s an industry with real prospects, because there will always be textiles – and they will always need cleaning. Textile care is not a manufacturing sector that can be outsourced abroad; I’m convinced of that. A garment may be produced elsewhere, but it’s cared for where it’s used. That makes the industry crisis-proof and vital to supply security. Textile care companies will continue to evolve, but they will always exist.

Andreas Schumacher: For me, it’s precisely this system relevance – something that became particularly visible during the pandemic. One of our member companies, a laundry serving care homes, told me at the time: “If I close my laundry, 15,000 elderly people in the region will have no clean linen.” That really brings home what’s at stake. So, there’s no alternative to continuing to train skilled workers – it’s not just about the companies, it’s about society as a whole.

Assuming we meet again at Texcare in November 2028 – what would have to happen by then for you both to say, “We’ve turned the corner in the recruitment crisis”?

Melanie Saner: My greatest wish would be that, by then, we’ve reversed the downward trend in apprenticeship numbers. In the coming years, larger birth cohorts will enter the labour market again, which could make it easier to find new recruits. It would be a major step forward if we succeeded in inspiring more young people to join textile care and showing them that our industry offers a secure and future-oriented career.

For me, the turning point will have been reached when companies across the board are once again training regularly and when the perception of the industry changes – away from a niche trade and towards a modern service sector with strong societal relevance.

Andreas Schumacher: I’m confident that within the next three years we’ll establish a broad range of qualification and career pathways – from partial qualifications and international recruitment to a dual bachelor’s degree. This will help us make entry into textile care more flexible and accessible through multiple routes, attracting more people to the profession. At the same time, pressure within companies will continue to grow as many will increasingly feel the effects of employees retiring over the coming years. This will influence how committed businesses are to training new staff. Despite all the recruitment challenges, the industry is economically strong – revenues are rising. The demand for textile care is there and will continue to grow in light of increasing sustainability efforts. Overall, I believe we’ve reached the lowest point and will see more apprentices entering the field again in the coming years.

Ms Saner, Mr Schumacher, thank you very much for the interview.

Profiles

Swiss Textile Care Association (VTS)

The Swiss Textile Care Association (VTS), based in Bern, represents around 200 member companies, including dry cleaners, laundries and suppliers. The VTS represents the interests of the Swiss textile care industry in business, politics and education, provides professional advice, and actively promotes innovation, quality standards and young talent through initiatives such as national championships. VTS members generate more than three-quarters of the total turnover achieved by the Swiss textile care sector.

German Textile Cleaning Association (DTV)

The German Textile Cleaning Association (DTV) is the central employers’ and trade association for the textile services industry in Germany. Around 800 laundries, dry cleaners and textile service companies are organised within the DTV, together representing approximately 85 percent of the German textile care market, which generates an annual turnover of about €4.3 billion. The DTV represents the industry’s interests in dealings with politics, business and the public, advises on labour, tariff and social policy issues, and promotes innovation, quality standards and professional training through events, working groups and initiatives.