Reading time: 3 minutes

Combining a natural fibre with a synthetic one promises synergistic effects. The best of both worlds is intended to give the final product enhanced performance characteristics. This concept is well established in workwear and contract textiles. By combining cotton and polyester, work jackets and trousers, shirts and aprons, as well as bed linen, terry towels and table linen, are intended to achieve a long service life, optimised washing and drying behaviour and a pleasant level of comfort. This principle has proven itself: blended fabrics are essential in professional textile care. The reason lies in the specific properties of polyester and cotton.

Two ideally complementary property profiles

Polyester is almost an all-rounder. The fibres have high mechanical strength, are dimensionally stable and resistant to oxidising agents, acids and bacteria. This makes them resistant to the substances textiles encounter during use and in industrial laundering. As the synthetic fibre absorbs hardly any water, it dries at remarkable speed – something every athlete is familiar with from functional underwear. In professional textile care, this property promises short dwell times in tumblers and finishers, as well as low energy consumption per item. Cotton also has high tensile strength and, in addition, good abrasion resistance. The natural fibre is resistant to alkalis and oxidising agents, which are common components of industrial white washing processes. Cotton also has a pleasantly soft handle, is absorbent and binds moisture within its internal structure. For this reason, it dries significantly more slowly than polyester and requires more thermal energy.

Hydrophobic and hydrophilic behaviour combined in one textile

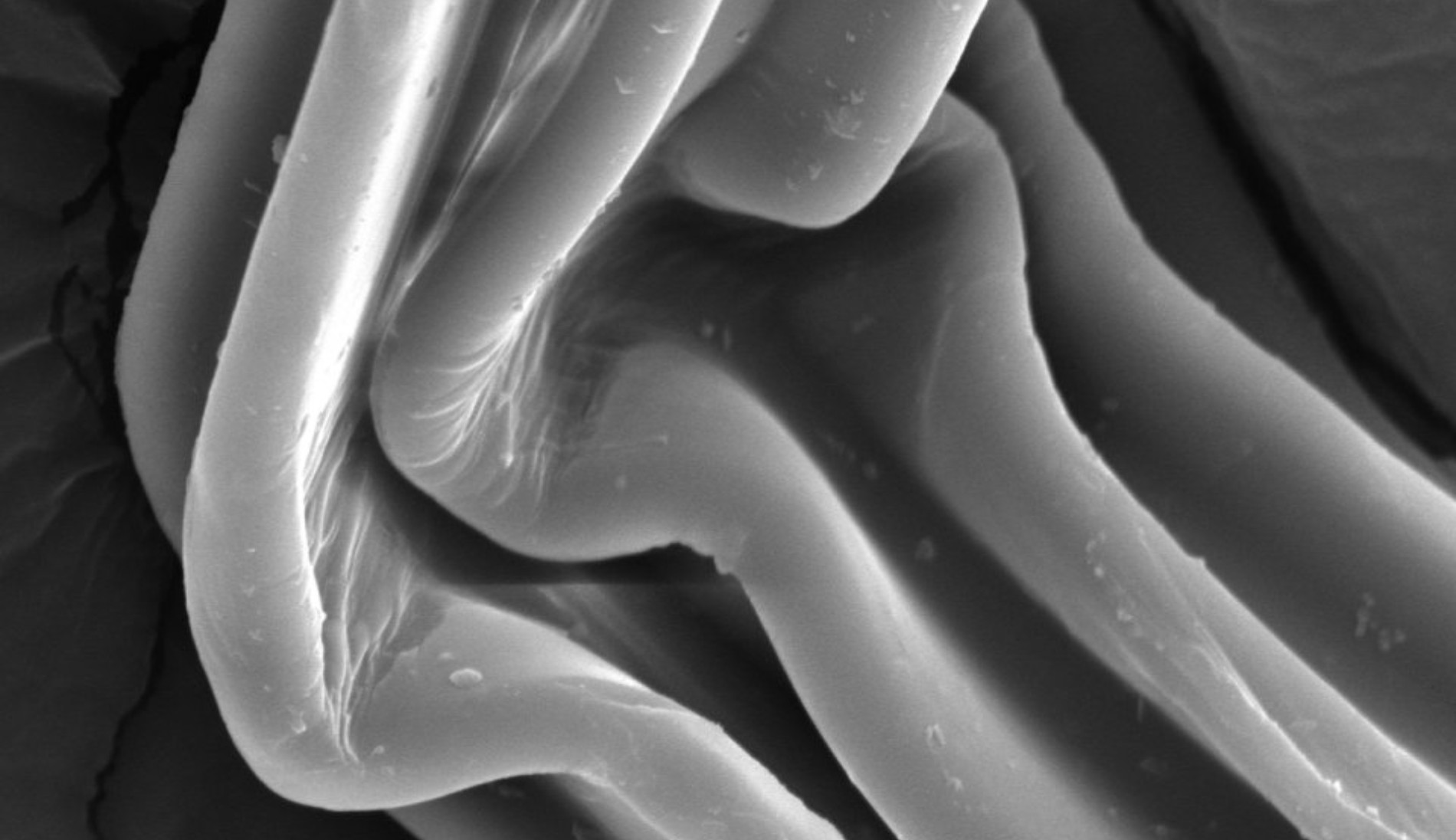

The very different drying behaviour of the two fibre components is rooted in the morphological structure and chemical composition of polyester and cellulose fibres. Polyester typically has a circular cross-section defined during the spinning process. Water molecules (H₂O) find little adhesion on its surface, as the thermoplastic fibre has a hydrophobic character and is therefore poorly accessible to hydrophilic water. This effect is familiar from pouring oil into water – the two substances do not mix. The morphological structure of the fibre also does not favour water absorption: the fibrils that make up a polyester fibre contain a high proportion of crystalline, highly oriented regions into which no water molecule can penetrate. Only the amorphous regions, which can be imagined as spaghetti-like tangles inside the fibre, provide space. However, the water absorption capacity of pure polyester textiles can be improved through yarn and fabric construction as well as through special finishing processes.

Cellulose fibre with an absorbent sponge-like structure

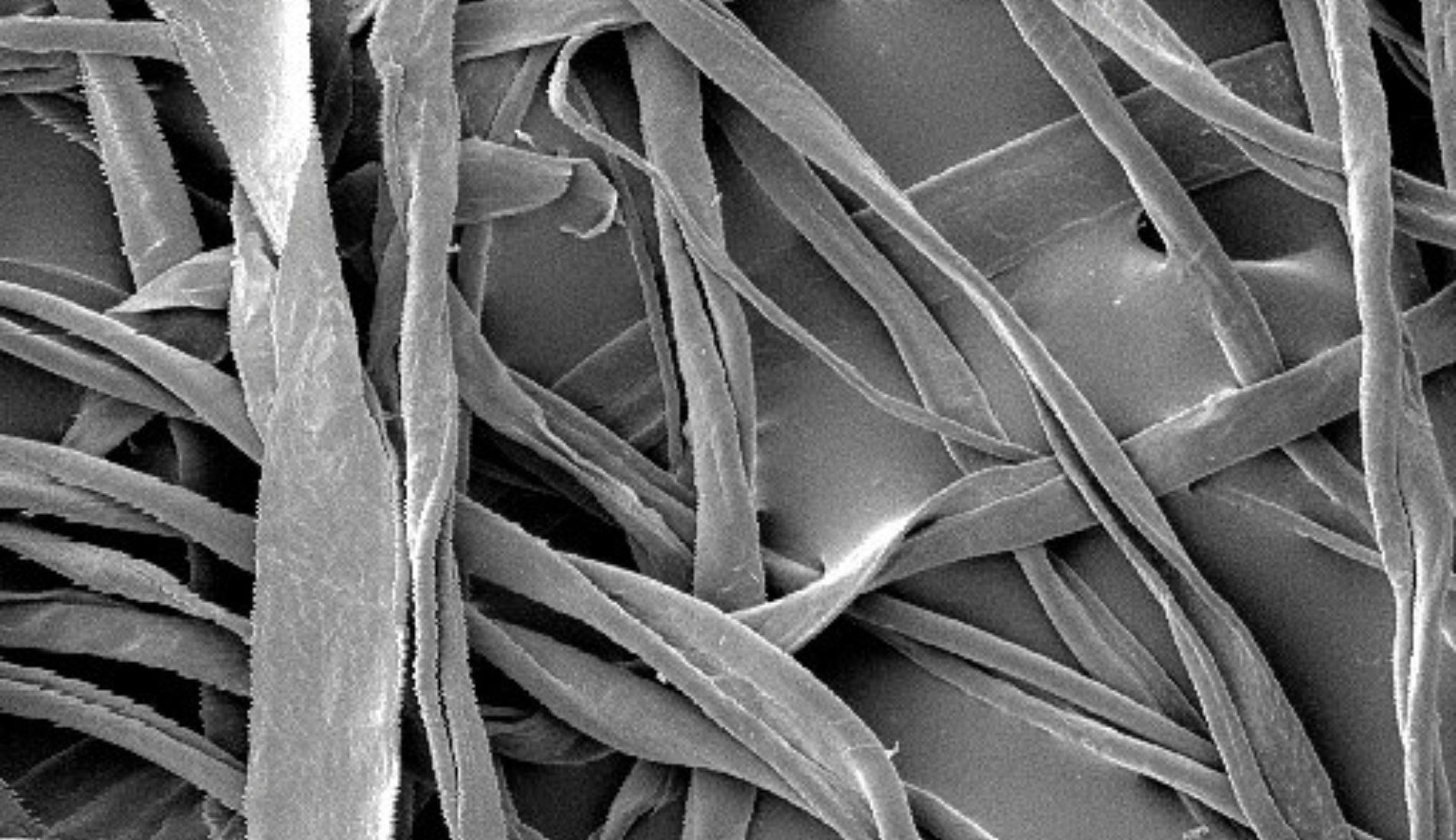

In contrast to polyester, cotton has a significantly higher water absorption capacity, influenced by several factors. Firstly, the fibre has a distinctive cross-section resembling a lens with a central hollow channel into which water can penetrate. From a morphological perspective, the structure of the fibrils creates pores or capillary spaces of varying sizes within the different layers that make up the cotton fibre. This internal structure makes cotton fibres accessible to liquids and water vapour: the capillary action of the fibrils draws liquid inwards, where it is retained in the pores between the fibrils. The cotton fibre therefore functions as a microscopic physical sponge with a complex porous structure. Chemistry also plays a role: each cellulose molecule incorporated into the natural fibre contains two bonding sites for water molecules. In addition, moisture absorption can be further enhanced by yarn and textile construction, as demonstrated by terry fabrics.

Critical from a surface temperature of 80 °C

The very different behaviour of cotton and polyester fibres towards water explains why drying and finishing blended fabrics is so challenging. While the synthetic fibre dries very quickly when exposed to dry heat, the moisture stored within the fibrils of the cotton must first migrate back to the surface. This process takes time.

However, it has one advantage: the evaporative cooling generated as the water evaporates protects the thermoplastic polyester fibre, whose glass transition temperature is around 80 °C and which transitions from a rigid to a rubber-like state beyond this point. Prolonged exposure above this temperature should therefore be avoided to prevent deformation of the polyester component. In practice, however, a different approach is often taken. Instead of the moderate drying and finishing temperatures recommended by machine manufacturers – and the associated longer dwell times – operators often increase throughput. The faster a drying batch is discharged from the tumbler and the more items pass through a finisher, the fewer expensive machines a company needs. This places the industry in a dilemma. Ultimately, each business must calculate for itself: the cost of purchasing an additional dryer or finisher must be weighed against losses caused by overdried, yellowed, faded, shrunk and strength-impaired textiles.