Reading time: 5 minutes

Water is the be-all and end-all of washing. It removes hydrophilic soiling from the textile, binds it and transports it away with the liquor. But as important as water is for cleanliness, the moisture is just as disruptive for subsequent processes, in particular for the use of the textiles. Therefore, the moisture has to be removed from the goods again – timed to match the output of the washing machines, coordinated with any subsequent processing steps and with the daily workload of the operation. In order for the processes to interlock smoothly, the drying speed plays an important role: the faster the water evaporates from the textiles, the more time a laundry gains in upstream and downstream processes and may even be able to manage with a smaller number of dryers.

However, wish and reality are quite far apart, because even after dewatering a relatively large amount of moisture remains bound in a batch of laundry. Thus, a 60 kg batch (dry weight) of pure cotton textiles carries around 27 kg of water after pressing, while terry towelling still binds around 24 kg of water. Even in blended fabrics, which after pressing have only a residual moisture content of around 25 to 35 per cent, at least 15 kg of water is still bound. Depending on the subsequent process, these quantities of water must be largely – or, in the case of condition-damp goods, partially – dried out of the textiles again. To do this, the water in the dryer must first of all be brought up to evaporation temperature; only then does the actual drying begin.

Take the construction of the goods to be dried into account

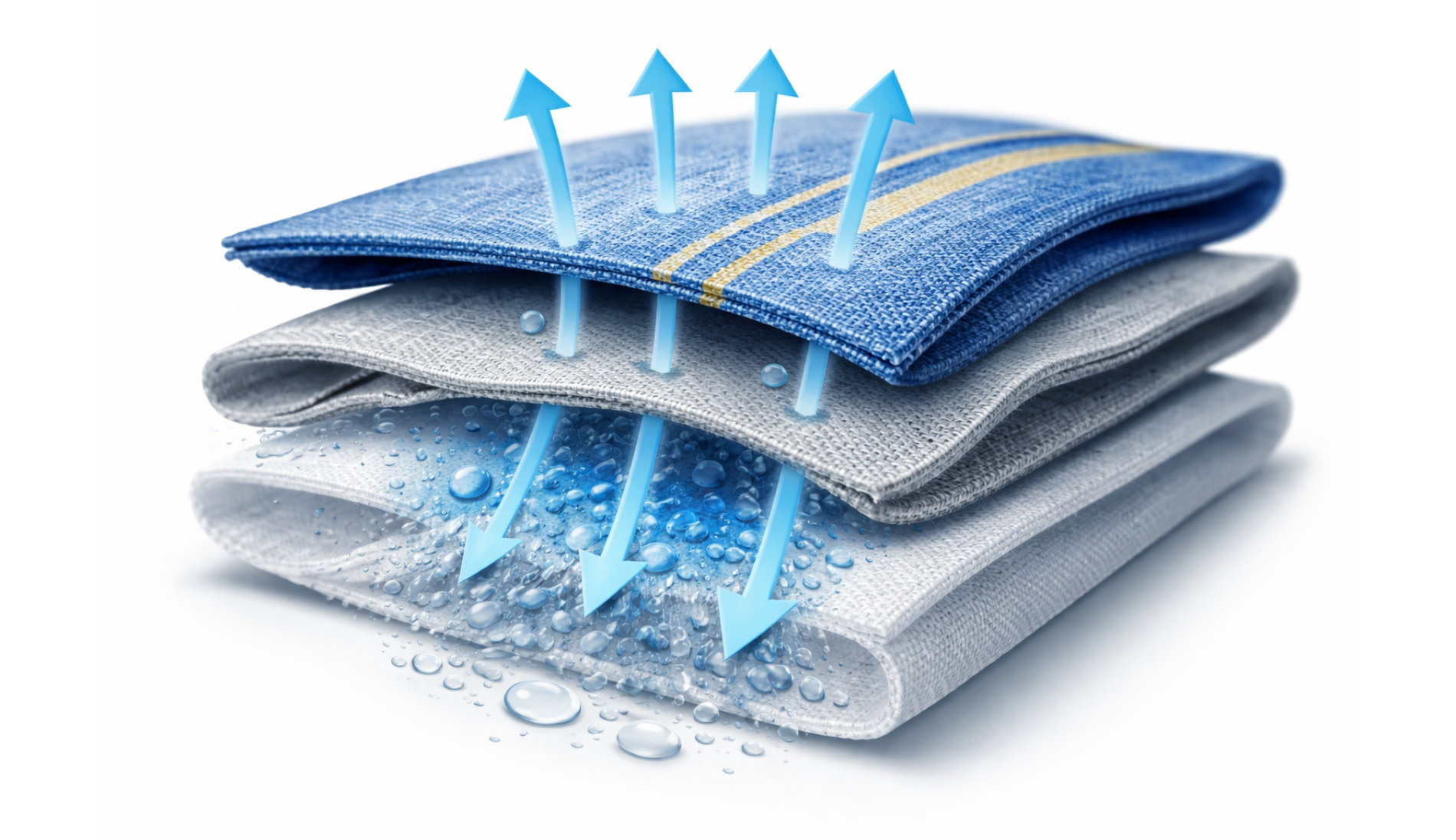

The challenge, however, is that flatwork and garments are not “one-dimensional”. They are hemmed, have pockets, lapels or embroidered logos where several layers of fabric lie on top of each other, which leads to a “drying gradient”: in such “sandwich structures”, despite high circulation of warm air, the water first evaporates from the outer layer. Drying of the “core” takes longer, because the water has to diffuse from the inside to the already dry surface. If drying is then carried out at a high temperature in order to accelerate the process as much as possible, overdrying occurs in the areas where the bound moisture evaporated first. This results in the complete removal of both the water adhering to the surface and the water chemically bound in the fibre. Apart from high resource consumption, this process has drastic consequences for the textile. Overdrying gradually makes the cellulosic textile fibres used in commercial-quality goods (cotton, lyocell) hard, brittle and causes them to yellow. As a result, the service life of a textile is severely reduced and it has to be replaced prematurely.

In addition, an overdried cotton textile disrupts the process, because when it comes into contact with the metallic dryer drum it becomes statically charged and then attracts particles contained in the air flow like a magnet. These foreign substances deposit on the surface and thus undo the clean washing result. Above all, however, there is a danger associated with continuously overdried cellulose fibres: thermal degradation of the fibre produces significantly more dust, which in the worst case can self-ignite and lead to a feared laundry fire.

Sensor technology for residual moisture measurement

For more precise control of the drying process, infrared moisture sensors are installed in the machines. By continuously recording the residual moisture in the goods, and in some cases also in the exhaust air, the optimum point in time for ejecting the batch of dried laundry is to be determined. However, this solution also only works with limitations. If only dry surfaces are passed in front of the sensors, the machine ends the process and ejects the goods, even if seams, hems and the like are still damp. The same is known from drying laundry of different weight classes and bulky cotton terry textiles. An IR moisture measurement can therefore be inaccurate if it only determines the “dryness” of the loops. Sensor technology alone is therefore not reliable; the experience of laundry experts is always required to optimally set the drying process. Depending on the type of goods, a short post-drying time is often used, during which only the heat stored in the textile is utilised to evaporate remaining moisture.

Match finisher speed to the goods

Finishing workwear, professional clothing and protective garments also requires the experience of a laundry expert, because for good reason no moisture measurement is installed in the machines. Loading a finisher with short-, medium- and long-cut garments leads, despite constant air movement, to continually changing residual moisture within the system. This effect is further intensified by processing different materials. For example, Tencel blended fabrics have a higher moisture absorption than cotton blends and therefore carry more moisture into a finisher. However, lyocell fibres dry faster than those made of cotton. When a finisher is loaded indiscriminately with such garments, either the regenerated fibre is dry while the cotton is still slightly damp, or the natural fibre is dry and the synthetic cellulose fibre is already overdried. For this reason, processing mixed batches is avoided in a laundry. Instead, similar types of goods are grouped together and the finisher speed is ideally adjusted to their specific drying behaviour.

Special characteristics of heating media

The difficulties in controlling a drying and finishing process occur regardless of the type of heating used, which in industrial operations is carried out using steam, gas or thermal oil and hot water. In special cases – including the operation of a laundry in a nuclear power plant, smaller laundry volumes or the use of a heat pump dryer – electrical energy is also used to generate the high temperatures. Each energy source has its own characteristics, which are taken into account in an operation’s purchasing decision.

Gas

- Gas burners generate heat when it is required; during idle times they are switched off.

- Gas can generate higher temperatures than steam.

- The evaporation capacity is higher.

- Heat generation takes place directly at the dryer and finisher, which minimises performance losses.

- The burners react – like on a hob – directly to changes in gas supply, enabling precise temperature control.

- Gas prices have been volatile for several years and have a direct impact on operating costs.

Steam

- Steam is generated in a boiler that runs continuously during operating hours and consumes resources (heating oil EL, pellets, biogas, hydrogen).

- Heating with steam leads to time delays, as steam has to be conveyed from the boiler house to the dryer or finisher. This also results in performance losses.

- A steam boiler generates steam at a specific pressure level, which makes temperature regulation more difficult.

- Drying with hot steam results in a softer handle, as the moisture bound in the steam can condense on the textile surface at appropriate temperature differentials.

Electrical energy

- Operation with electrical energy is possible for exhaust air dryers with a capacity of up to around 100 kg dry weight and for dryers with heat pump technology up to a loading capacity of 20 kg. Drying cabinets are also heated using electrical energy.

- Electric heaters allow good temperature control.

- The heat-up time of an electrically powered dryer is longer than with direct heating using steam, gas or thermal oil.

- The energy costs for operating an electrically heated dryer can be reduced by installing photovoltaic systems.

There is therefore no one-size-fits-all solution for drying processes in a laundry. They always require careful planning and the experience of experts.